As I write this, many memories come back. When in Harare we collected old CDs with photos from our move to Zambia onwards. I only have a few limited photos from before that, especially of our farms in Zimbabwe. Digital technology is great, no need for getting photos developed or store in physical albums. How few of us men did that being from a generation whose productive years were pre-digital? We relied on our wives!

Now I have arrived home, I have had the time to reflect on our Zimbabwean trip and consolidate my opinions. Every time I met up with old Zimbabwean friends, they would all ask me what I thought of present-day Zimbabwe. I would fluff it by saying the people are great while the country is a mess. Of course this is the truth, just not the full story. I emphasised that the rubbish around the capital was beyond belief.

It dawned on me while everyone saw the rubbish, it had little impact on their daily life as it was something that was just there. The same with the potholes. Yes, many complaints. More a conversation topic rather than something anybody was taking time or thought to remedy. Complaining is a way of life in Zimbabwe, I can understand why.

The traffic, they did take exception to as everyone's temperature rises in traffic especially when much of the cause is due to the ignoring of the traffic rules. Importantly, those of the northern suburbs give little recognition or at least little care of how those that live and work in the southern part of the city. The northern suburbs are still generally clean with smart well cared gardens behind walls. Further south the roads are jammed especially morning and evening with vendors closing the inside lane in trying to attract passing custom adding to the confusion. I would probably have the same attitude if I lived there. In becoming “an outsider”, you suddenly take cognoce of things you would take for granted if you were a resident. It is how the world is.

“Anything in this world becomes normal if you enjoy or conversely endure it long enough. Both directly opposing situations can be found within a single country population” Peter McSporran

Crashes in the city are common, once again a common occurrence rather than an exception. They were surprised to hear I had lived in Portugal for four years and had never been stopped by a policeman let alone spoke to one. They are from time to time visible here which reminds you to behave on the road. People rarely drink and drive here, although the Portuguese think wine with a meal is not drinking. When driving, they limit their intake.

I am now going to bring up a sensitive subject with a conclusion not everyone in Zimbabwe will agree with. Just like the rubbish they are aware of, it has become part of everyday life. If they're like me, they may stop reading, as I do from time to time if I do not like what is being said, even if what is written is the truth. Of course, the following thoughts and conclusions are mine.

One of the other things that became obvious is that to really make money you have to be an entrepreneur in Zimbabwe. Salaries, especially in RTGS (Real Time Gross Settlement) which devalues daily although the official rate is close to being only 60% of the black market rate, are low. Of course, higher-paid employees change their RTGS into hard currencies. The lower-paid workers are not in a position to do so. Cash is king, all electronic transfers, the norm, as there is little cash, however, have charges high bank transfer and other charges. For very small mobile cash transactions the charges could be greater than the item cost. On top of all this is the 2% tax on every transaction. It is easy to see that those who get access to the official rate can make vast fortunes by selling on, then rebuying again at the official rate. In Zimbabwe currency terms, this is history repeating itself. I hope there is someone out there that will correct me if I am wrong?

Even people with employment have some side enterprise, Zimbabweans have become a nation of “wheeler-dealers”. The problem is that employed people in Zimbabwe’s statistics include subsistence farmers and their families, vendors of any kind, including even the lowly street tomato seller, hence the claimed figure of only 7% unemployment. Meanwhile, something like less than 30% is actually employed with a wage or salary. Should the 7%, if we are really honest, read closer to 70%. Think about it. An above average smallholder selling a tonne of maize would only give him an annual income of some $240, which after delivery he may have to wait several months to receive. Hence the term subsistence, the grow what they can eat to survive. Teaching people how to suck eggs here.

In my reflections, the most worrying thing was the acceptance of corruption in everyday life. To this extent, many may not recognise that they are actively involved in corruption promotion, even if in some cases very petty. As the state along with its officials is corrupt, the man on the street becomes corrupt just to survive within the system. They have no choice in a state that ignores their vote or rights. They adopt the means to survive, thus consolidating the problem. Little people can have great power in a corrupt state.

“Corruption in any form usually involves the use of a person in power, no matter how insignificant that role may be, to procure documents, legal or illegal, influence legal procedures or outcomes in your favour, receive leniency, secure tenders especially from Government, secure goods, circumvent taxes, getting information giving yourself an advantage over the poor thus compounding their poverty and access to services and fair treatment. Corruption when endemic is found in both the private and public sector.” - Peter McSporran

Shockingly, access to your legal rights under the constitution become something you have to pay for. These two phrases I came across very often during my stay there:

“While in Africa do as they do.” ‘They’ here, means everyone.

“That is just the cost of doing business here. We build it into our cash flow.”

Of course, someone pays for this, that being the poorest members of society compounding their poverty. Maybe not in the form of hard cash out their pocket, rather in terms of access to health, education and other services considered a right in most countries.

Operating in Zimbabwe, as a failed state, as my good friend Peter Richards reminded me this week, you require the following aids to do business. They include, but are not limited to:

A friend. Read this as a low-grade contact in one of the many Government departments. He is normally of fairly low status and will help you for little or no reward to expedite your legal right or request for information. A meal or a beer may be an ample reward, maybe just your friendship will suffice. Everyone needs a friend.

A runner. As there are large shortages of both business inputs along with the day to day comforts required in the home, runners can provide the required goods quicker and cheaper than going through normal channels. Their documentation along with import taxes can be bona fide, their services are substantially quicker and cheaper than conventional means. Of course, this will not apply when the end custom is making a cash purchase or be it for smaller household items and personal goods. Those running a proper business need the documentation which generally the runner can provide.

A contact. This is now a more senior person with the power to provide something or even expedite an import, licence or help with a minor legal problem. He will definitely need payment or a large favour in line with his service. Remember corruption does not always need cash, it can be kind.

A fixer. This is someone senior in power requiring high reward. He may have political power to stop your harassment, give access to land, planning permission or even resolve legal issues circumventing the courts. He may even be entrenched in your business as a sleeping partner.

I can understand the petty corruption for people to survive in Zimbabwe. However, the state corruption will need to be resolved for the country to reduce costs, stabilise the currency, attract foreign investment, and access aid for development (rebuild the country's infrastructure). Then life can slowly return to normal. A huge task requiring much willpower. Of course, many businesses may not survive when there is a level playing field, where cronyism and bribes are no longer business tools.

Here I am claiming corruption has almost destroyed the country with the poorer suffering the most. How can I quantify this to try and support my point that the poor are the losers? I decided to do a wage comparison, maybe it is subjective, but it will amplify the point on how the poor are the losers.

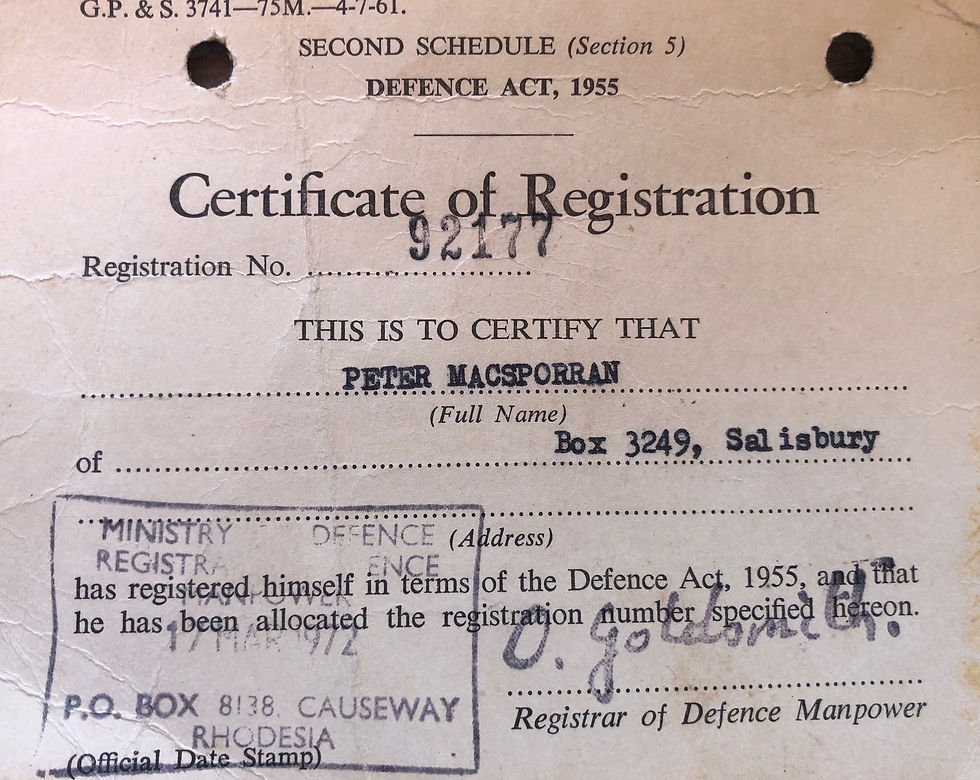

I thought about what a farm worker would earn in the 1970s in Rhodesia in comparison to what he earns now in hard currency. Then compare it with what I was earning per week as a farmworker and what I would earn now in the UK. I say this is a subjective, but fair comparison as the cost of living has become very high in Zimbabwe despite low wages.

In 1970 I earned £21 for a forty-four hour week in the UK. That is 48 pence per hour. The lowest-paid farm worker in the UK in 2021 now makes £9.50 per hour. This is a nineteen fold increase.

When I came to Rhodesia the average earnings for agricultural workers was Rh$12.75*. This was equal to GBP£12.75 as the Rhodesian dollar was worth one pound. On top of this, he also received his weekly basic food requirements which included maize meal, a protein, salt and in many cases cooking oil and sugar. His salary is now ZW$4,600 or the equivalent of USD$54 at the official rate or USD$31 at the pertaining rate on the street. Let's convert the dollar to pound to compare like with like, that is at the official rate he is receiving GBP£39, at the street rate he is receiving GBP£22. At best, a three-fold increase at the official rate, at worst less than double without the food ration.

While the Zimbabwean GDP in recent years has been declining, the rich can only be getting richer from the poor, with no new income being generated by the country. Is this correct?

I am sure there are many counterarguments, I welcome them or comments? The truth is a few get very rich, while the poor get poorer in a corrupt society without the rule of law.

Settling into my New Way of Life

Once I moved into my own cottage furnished by cast-offs from my employers. My $70 per month was required to feed myself and provide entertainment. Farm managers and assistants in Rhodesia, as is the norm today, relied on their bonuses to survive and save. Most had one ambition that was to possess their own farm. I was no different. I had been told not to expect a bonus in my first year, so had to live within my means. I would place my weekly meat order with Mrs Smith who would arrange to collect it from Orr’s butchery. They had a shop in Avondale and Chisipite then. Their prices were above supermarket prices, but the convenience outweighed the savings. I was allowed to take a couple of hours off when not busy to do my grocery shopping. This was done at Harvey’s store in Mount Hampden or at the OK Bazaars in Greencroft. I see there is still an OK there, Harvey’s as we knew it, is long gone.

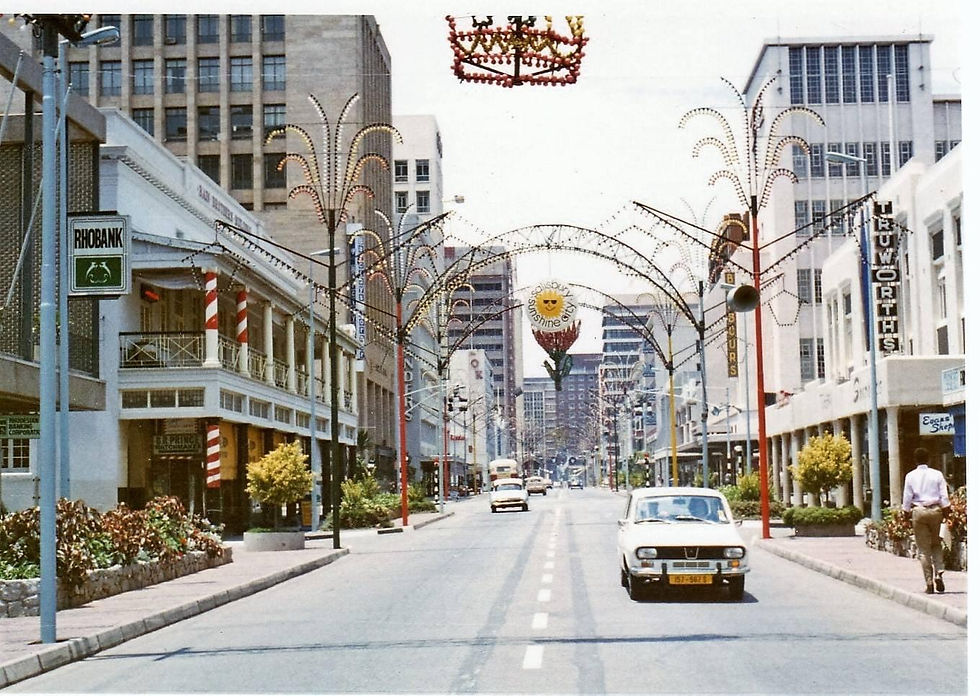

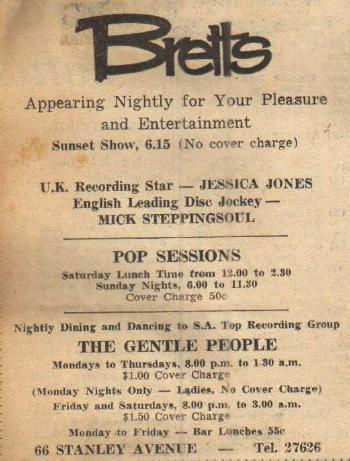

On my weekends off, I would spend Saturday night at the Fox’s in Marlborough. They would feed me well before I returned to the farm on Sunday night. They were so generous, I feel I never really recorded my appreciation to them. Selfish youth. I was aware of the existence of nightclubs as they were called in Rhodesia including Bretts, Le Coq D'or and La Boheme. With no trust in the Wasp starting up I was afraid to take the risk of being stuck in the city centre.

On the farm, other than the Sears, who provided me with a meal on occasion along with the Smiths, I did not meet my neighbours. In fact, it was almost a year before they knew I had moved to Umzururu. I was unaware of the Club at Nyabira, which was not at Nyabira rather beyond, therefore I did not become integrated in the community. My closest neighbours were Boss Lilford, one of the powers behind the Rhodesian Front, who had to be avoided at all costs due to his unpredictable temper never being separated from his sjambok. He had further protection from an aggressive goose that was in his company most times you visited his farmyard. His son Chesney, was on the next farm closest to my cottage. He was to be avoided too as, so I was told on good authority, he was an alcoholic and had some sexual tastes out of the conservative norm at that time. That left me with Lilfordia School, which was only a few hundred metres from my home and the Du Toits of Wild Duck farm, which was about 4 km from the cottage. At a later date when I moved to Darwendale, I became great friends of the Stokes, Burgers, Bells and Walters who were all along the western boundary of the farm. Unfortunately, there seemed to be an invisible barrier along the Nyabira road. Those to the east found entertainment in Salisbury, it being some 30 km away while those in the West found entertainment at the still undiscovered club.

The one night shortly after I arrived on the farm, the farm secretary Mrs Sears invited me to dinner. As the evenings were spent at home with a black and white TV watching the occasional Mannix or Perry Mason reruns with the National Foods High School Quiz, the highlight of the week to excite me, any invite for a meal was attractive. The RTV news ran for about an hour in those days. I got permission from Hamish to use the motorbike and duly set off down the road to Innerleithen, a farm owned by the Smiths near the main road some 20 km away by road where the Sears resided. On my return trip just a few kilometres from the Sear’s house, the motorbike had its last gasp, stopping suddenly and refusing to start. What to do, go back and wake the Sears for help or push the motorbike home. Stupidly, I thought it unwise to wake the Sears so to my regretful hindsight, I pushed the motorbike some 20 km home. It does not pay to be shy in Africa, lesson learnt.

The Many Guises of Consultancy

When I farmed in the early years, I used to hold consultants in contempt. Surely if I was the farmer, I should know my trade. Why ask others? Was it a mixture of arrogance along with vanity or just plain ignorance? I should have understood that my agronomy advisors, although also salesmen were in a way advising me, therefore were free consultants. These included Frank White, Derek Christmas, Doug McClymont and Brian Campbell. Meanwhile Joe Pistorius and Richard Wingfield, then working for CONEX, visited the farm regularly.

When Ian Gordon bought the farm next door to me from his ex-father-in-law Bill Gulliver, he purchased a farm that had been mined by growing continual maize on sandy soil. Bill was a dam builder, not a farmer. Despite Ian’s bid or perhaps his connections being better than mine in getting access to the farm, he was to prove to be an enlightened farmer. His first few crops were poor, which he quickly recognised were due more to the fertility and structure of his soils rather than his management. He employed Colin Blair as his agronomy advisor and low and behold within three years, probably his second rotation under tobacco, he was out yielding most of the area. An eye-opener on the benefits of a good agronomist consultant.

When we moved to Zambia, we ensured we should have good agronomy advice both for ourselves and our scheme members. Rob Garvin and Doug McClymont were our chosen first callers, Rob being retained by us. Of course, personalities come into the equation with some of our clients being very happy with the service while others, albeit a few, would blame their mistakes on the consultants. Most people that have crop failure often blame others or the elements. The elements of course can often be the culprit, less so the consultant I have found.

I soon learned there was another type of consultant. Before leaving Zimbabwe in my partnership with Ernst and Young we tendered for larger jobs within the region. These consultancies were aimed more at grandeur schemes or businesses beyond the good practical experience on offer from our agronomists. They very much involved business models supported by graphs, fancy cloned pictures and cash flows which would always be made positive. Luckily we rarely got past the tender stage. However, it opened my eyes to the world of international consultants. I should say that their best tool was “cut and paste.”

As our business grew in Zambia we were called on to look at similar large schemes. I determined we would stick to the practical side and to what we knew. The reason I am writing this today is while in Zimbabwe I picked up CDs with some of our historical projects, supported with pictures. This one particular project has always stuck in my mind for two reasons. Following our work for the Libyans in Zambia, they wanted me to visit their mango, limes and soya growing project in Ghana. This was owned by Ghana Libyan Arab Holding Company (GLAHCO.) I had never worked in West Africa and therefore was reluctant to take up the visit, especially as I knew nothing about mangoes or limes, nor the climate there.

They insisted, with me soon finding myself in the Golden Tulip Hotel in Accra, which they owned. Before leaving I was handed annual reports, copious in nature, provided by a retained international German consultancy. Why would they want me, when they were paying a retainer to perceived real experts some $300,000 a year for advice?

Before departure, I asked them to dig soil pits at least a meter deep. Funny when you ask people to dig meter deep pits, they rarely go down beyond half a meter. There are exceptions but rare.

The farm was close to the mouth of the Volta, at Sogakope. Just by travelling to the farm, I could see there were huge problems with the soils. Plant growth was very stunted with bare, whitish clay visible on the surface. Despite the soil pits being shallow, mottling appeared at 25cm meaning the water table was very high most of the year. That is, it got waterlogged in the rains and became concrete in the dry season. The trees were stunted and visibly stressed.

I include some remarks from my report as they pertain to many agricultural businesses even today. I will include them as quoted below.

Before doing so I should mention the two reasons why I remember this trip so well.

The first was because although there were extensive notes and reports from the international consultants supporting the business model there was no practical input hence the project's failure. Much money does not always provide good advice in fact it can be adverse.

The second incident I remember from the trip was when at the bar in the Golden Tulip I was approached by a lady asking me if I wanted a massage. This being a euphemism for other services. On my refusal of her services she informed me I should have been grateful for her approach as I was an old man. That was the first time I was called an old man, I was still under sixty. How old must you look be when a working girl calls you old?

Some quotes from my report, of course, in diplomatic language for the client:

“Most of the soils on the property are generally just not suitable for intensive crop production and as much of the area is prone to waterlogging even rain fed crops would be unlikely to be viable in those areas shown outside the areas on the map demarcated for irrigation. The area chosen for the mangoes was not by accident, that is the best area of a very limited choice, notwithstanding the size of the property.”

“As professionals, we have trouble understanding why a plantation crop was established without the adequate irrigation infrastructure in place to enable it to succeed. What could have been the rationale behind this?

“Unfortunately agriculture primary production generally offers a poor return, a required long-term outlook and is high risk (market, weather, crop disease) for an investor. Most agricultural projects offer at best a 10% IRR. It is therefore essential to select your farming enterprise’s location carefully to enable you to achieve high yields and offer you an area large enough to operate at the required scale to ensure your overheads are met.”

In 2011 Gaddafi was overthrown ending the need for our services.

* Harris Department of Economics, University of Rhodesia, Salisbury

Disclaimer: Copyright Peter McSporran. The content in this blog represents my personal views and does not reflect corporate entities.

Comments