What Is Stalling Agricultural Development in Africa?

Much of what I am writing about this week is not necessarily directly related to those I have worked for or with. Rather, it is from my personal observations and experience over the past twenty-odd years since I started working in commercial agricultural development and funding. As I claim, not all will agree with my views.

I think what sparked off this particular trend of thought was what I would call the illogical methods of tackling climate change by introducing theoretical targets unlikely to be achieved. It almost seems that the politicians have coerced scientists to come up with a number required to halt climate change to indicate they were making efforts to save the world. The more radically green these advisors are, the better. The more impractical the policies, the better.

It is envisaged, not guaranteed, that these targets if met would halt the present trends of global warming. Is this a fact? I agree we humans are contributing to the destruction of the earth’s environment as we know it, but we are far from the only contributing factor. These theoretical numbers appear to have ignored all the possible risk factors, such as sovereign politics, war or even the human or financial costs. We farmers know not to leave one risk factor out of our budgeting models from the climate, to the market, in Africa, this includes the political risk. This last risk has unexpectedly come as a surprise to European leaders who spend billions on intelligence every year.

“European leaders cannot blame the energy shortage on one man, Putin. The blame surely lies with them in their self-centred individuality in trying to proclaim to their peers that they were actually meeting their clean air targets.” - Peter McSporran

This was recently admitted by European Commissioner, Thierry Breton:

“We prefer to import from third countries and close our eyes on the environmental and social impact there, let alone the carbon footprint of importing.”

Is not the hard rock lithium mining in the DRC for all these green cars an example of this?

The point here is the climate battle is being fought using numbers generated by discounting the holistic impact or the practical implications. People say numbers do not lie, but they are very dangerous if misused.

We found in the Rhodesian war despite the same lesson having been learnt in Vietnam. Numbers on a board, even if backed up with bodies, do not win a war. Numbers generated on a board, be it a cyber board, will not affect climate change. Long-term practical solutions are required, implemented over time to lessen the impact on employment, production or even the ability of the individual to keep themselves warm in winter. I do not think we have even thought on how we will dispose of the new types of waste we are creating at the so-called ‘life ends’ of these new technologies.

As an aside, Rozanne has been flagging to me the extent of the leaks in the UK water supply system, the effects of which are exacerbated due to drought. I was shocked to see a figure of 23%. Almost one in four litres, the solution being it would appear rather than fix this, impose a hose pipe ban. Then I thought about how much energy is used to treat and pump water, all of this precious water lost through these leaks. Must be many thousand mW used for pumping and purifying each year. The cost of pumping those lost litres is in the customers hand not the company’s, so no incentive to fix. So enforce those selling the water to fix the leaks or lose their licence, save water and save energy, both fast becoming scarce commodities. Maybe it is more exiting to talk about the damage cows are doing than leaking pipes.

“How mad would you look if you poured every fourth pint, which you just paid for, onto the pub’s floor?” - Peter McSporram

Back to numbers. I was becoming aware for the last few years of my working life, despite feeling I still had something to contribute in my field of expertise, African agriculture, that my days of participation were waning. Latterly, I used to think of myself as a dinosaur in the changing environment around me which appeared to be moving further away from good management practice into a world where reports and exaggerated theoretical targets were the driving force. I felt it fast was becoming like the NHS. Too many captains not enough sailors. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG), social or impact reporting were fast becoming the main driving force. Reports and studies, hugely time consuming, becoming of paramount importance. The fieldwork may have been collected by someone with knowledge, often tweaked, with the actual compilation of the written material being done by someone who had never strayed far from their desk, based in some capital city preferably as close to the main funders as possible, rather than the benefactor. Their most important skill being capable of producing nice tables, supported by colourful graphics altering the ‘numbers’ to fit the story, the sale pitch so to speak. The thing was that these people knew so much better than I or other on-the-ground practitioners on how to compile such reports to satisfy their boards, fund managers, donors or Development Finance Institutions (DFIs).

This feeling of redundancy was not so much about others, rather my own state of mind. Since losing my farms, my satisfaction in life was trying to be actively involved in helping others to invest in African agriculture by supporting the brave modern would-be pioneers. How satisfying it was to successfully contribute to the success in Zambia by bringing many farmers to that country including sourcing the required funding. Like the forcados in Portuguese bullfighting, to invest your own money on farming in Africa you have to either be brave or stupid, probably both. As we know a farmer or agricultural businessman in Africa not only faces the same list of risks outside of his control as the farmers in the rest of the world, they have to further contend with unclear laws which enhance corruption in their interpretation along with local and national politics. Generally, the banking system does not work, security of title being one of the major stumbling blocks here. The funny thing, over the years, I have come across many people who would in everyday life be considered stupid, or at least ignorant, who have been exceptionally successful at business in Africa.

As part of my contribution, I had an extensive network of agricultural personalities including experts, which I can safely boast were second to none both active in business and working as professional advisors or scientists, leaders in their respective fields. Soil, agronomy, livestock, irrigation, you name it. Reliable contacts, most with proven track records on their capability.

My problem was the creep, no rush of what I can only describe as ‘smoke and mirrors’ both in business reporting and impact assessments including projected targets. We know ‘fudging’ is common practice in corporate financial reporting and environmental assessments even in Europe. That is; annual financials are manipulated even in a poor year trading to be positive. Forecasts are overstated, while the impact on the environment is understated. In producing these sorts of numbers, a risk assessment is done only in their short-term effectiveness. Are the lies worth the benefits? To the individual, not just the company. I have no doubt those releasing the sewage into the ocean in the UK will have done a risk assessment and cost-effectiveness on this despicable ongoing action despite huge profits.

Balance sheets are manipulated by professional CEO’s, many being ex-bean counters or those with the support of such professionals, to ensure short-term profits on paper to warrant the reward of healthy bonuses for themselves. Mostly not illegal, although, often verging on fraudulent. Land values and improvements in agriculture were a favoured tool in the balance sheet while increased livestock valuations could be captured in profit and loss. Long-term sustainability for the benefit of the entity or its shareholders often of secondary consideration. The ability to create short-term window dressing has become a recognised talent amongst some professionals especially when raising funding from shareholders, donors or lenders. Often boasted about in some upmarket hotel bar in an African city with a large 4x4 parked outside while the manager in a field is desperate for a new tractor to help harvest his crop.

Impact numbers will always remain a mystery to me, there are some accepted standards but as far as I can see, these are always produced by the backroom boys, never the people on the ground. Despite this, normally one can come to some agreement on the impact numbers short term, but for me, the true numbers would be; What is the impact in the future? Say even five years down the line, let alone ten years. Little interest is shown by funders, especially donors after a program is completed. Run its timeline, end of story. To attract funding it is important; impact numbers must be seen to rise. Just like profits in a business, annual reviews are like balance sheets to impact investors. Many billionaire donors, such as Gates, love impact numbers.

As the imposition of first-world rules and reporting standards, including required content is imposed on a developing continent such as Africa, it creates barriers to development. Rules on ESG are often generated on a desk built on perception in some city using IFC or World Bank Standards suitable for the first world rather than the practical or financial ability for them to be implemented on the ground. This desktop may well be in the driver's home since Covid-19, unlikely to return to the office unless forced to do so. Therefore no interactive live discourse or exchange of ideas across the room. No walking over to the wise old fossil in the corner for some practical advice, all theory, now and ever more so.

Due to land access and lack of funding, it is extremely difficult for individual farmers to invest in commercial agriculture in Africa. Economies of scale are just so important, not just individual but group numbers, for input procurement, capital equipment, machinery servicing and importantly for a dedicated banking system along with logistical and marketing access. In Zambia, they have made farming blocks available. At the time, we moved the Zimbabwean farmers North, fortunately, there was enough semi-developed unused titled land to initially get a scheme off the ground. Those designated blocks are now being developed. An example is Nagasanga (Serenje) now a large farming hub that was virgin bush twenty years ago. The first few individuals struggled there but as their numbers have increased, despite the hardship, they have attracted new investors, tarred roads, dams and power. The same can be said of Mkushi originally designated away back in the fifties as a commercial farm block which in the late sixties and seventies attracted exiles from Tanzania, Kenya and the DRC. After a tough time was had in the eighties and nineties, Mkushi is now the envy of many African countries producing a large portion of Zambia’s maize, wheat and soya. A thriving community employing thousands.

Rhodesia was opened up in this manner, a block at a time. The last one I think probably was the Middle Save Scheme. I have not seen any such schemes replicated in Africa. The question must be why not? My gut feeling is we will continue to play with impact numbers and reports achieving no long-term new successes, rather vying for control of the limited existing successes. A playing field offering access only to the corporate or fund manager not the local farmer nor offering significant expansion of food production.

Surely this is a blueprint of the required model rather than one based on ESG, impact numbers and endless reporting in the required format. I never met a farmer, be it in Scotland or Zimbabwe, that did not find the simplest form a major headache.

This week it was further confirmed, I am out of my depth in this modern world. I learnt that lesbians who tried to join the Pride Cymru march in Wales were escorted away by the police as it seems the pride organisation think that lesbians who refuse to sleep with trans women are morally deficient. Freedom of choice seems to be a fast-diminishing right, even for those who have just recently achieved rights.

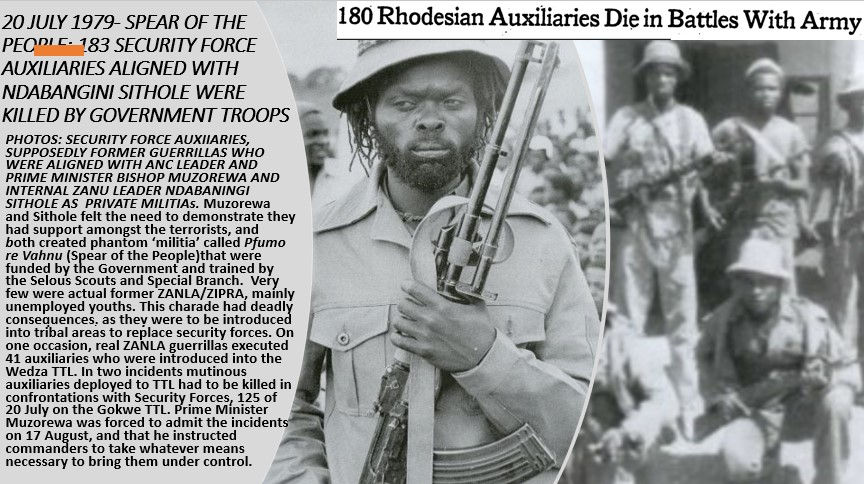

Pfumo Re Vanhu Encounters and A Bloody Contact

SFA (Security Force Auxiliaries) or Pfumo Re Vanhu (Spear of the People) were black private militias loyal to the participants of the internal settlement formed in the latter part of the war. These people, with very basic training supervised under Special Branch, were released into aiding the war effort, although we were soon to learn their loyalty was very much to their leaders’, Abel Muzorewa who led the UANC (United African National Council) and Ndabaningi Sithole who led the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) rather than the country. The numbers were said to be some 2,000 by mid-1979, rising, it is said up to nearly 10,000 by the end of the war. I think this figure is much exaggerated. There were the other ZANU (PF) and ZIPRA, still fighting who were said to have some 30,000 combatants. Probably also exaggerated, although, that number was said to have left Rhodesia to join the CTs.

Anyway, we, both black and white in the Rhodesian forces, looked at them with dislike and mistrust. Their training was rudimentary, to say the least, and therefore, as was to be proven, their discipline exceedingly lax. In our area of operation out of Enterprise with PATU, they admittedly had some early successes against the enemy. As their numbers grew so did the claims of atrocities, including rapes, raids on stores and other thefts mostly by armed intimidation or torture.

Sure enough in mid-1979 at 4 am one morning I found myself along with army units and other PATU sticks about to launch on a combat operation not against our normal enemies but our would-be allies who had gone rogue in that area. What a mess, I thought, bad enough fighting our sworn enemies, now we had to go into combat against those that were meant to be on our side. Our orders, if possible were to ask for them to surrender rather than shoot on the spot. Of course, as normal in war, the shooting starts first. Luckily, many surrendered without a fight, particularly where I was, while in other areas the SFA suffered heavy losses before surrendering. One way or another some of the SFA units continued to be armed and had some limited success even if losing one-for-one with the enemy can be called success.

Our call-ups continued and in late August, during Salisbury Show Week, I received my call-up papers to report for duty yet again in Enterprise. As I was about to start planting my irrigated tobacco crop at the end of that week, I got deferment for a week. One of my neighbours did go, Mike Bedford a successful cattleman who ran the ranch on Little England for the then Deputy Prime Minister of Rhodesia, my father's old school friend, David Smith. Off Mike went on his own, reporting to the officer in charge where he was assigned to a new stick which he had never worked with before. Later that week, on Friday the 31st, we heard he had been in a contact. Nothing new about that, except this time Mike had been wounded and one of his stick had been killed. What was sad about this was that the chap killed was a university student on his vacation, called-up as a Special Reserve. He had trained with the army as a medic, not an experienced field PATU operative. We old hands had many operational and combat years under our belt by comparison. Malcolm Bartlett, aged nineteen died that morning.

When we visited Mike in St. Annes Hospital, despite a shattered elbow, he felt more pain in his heart at the needless loss of a young man, as he felt by that time, we were involved in a lost cause just waiting for the final settlement. He said he thought the resting site was poor as it had high ground on both sides and believed the CTs were able to pinpoint their position as they had bedded down for the night near a fence line, an excellent guideline in the dark if the CTs had seen them at dusk. Not being the stick leader Mike had complied with the order to camp for the night in that vulnerable spot. At first light, their position was overrun. Sad that someone was killed, lucky more were not.

Mike at a later date was to be murdered by poachers on his own ranch in Wedza. His wife at that time, Beth, became a close friend in my ‘born again bachelor’ days and she relayed what Mike told her about the incident, much similar to what he recited to me at St. Anne's Hospital immediately after the incident. She has put his words, as she says into fact-based fiction, as an English teacher, much better than I could.

“They say that war is made up of the following two instructions: “Hurry up!” and “Wait!”. - Beth Bedford

“We had done both during the interminable bush war that we were obliged to serve in. Our group of four men had been sent out on a week’s foot patrol to a remote area, known to be seething with enemy soldiers. Three of us were old hands at this but our fourth member on that patrol was a youngster, a replacement for our usual comrade in arms. We were tired of hurrying, tired of waiting, tired of sleeping fully dressed, fully armed.

That night, in our usual circular formation, I had had the early watch, gratefully handing over to the youngster for the midnight watch. It seemed as though I had slept for seconds when I was shaken, waking fast but silently. All four of us lay flat on our stomachs, propped up on our elbows, each facing a different direction, rifles aimed into the impenetrable darkness, aware that we were not alone.

A twig cracked. Something rustled nearby. A soft whistle. Then the night exploded. My right arm collapsed under me, my rifle falling useless. A second later, the searing pain and warm wash of blood, a scream, shouts, people running, then sudden silence. The youngster was still beside me; still, bloodied, dead. My head swam, I was losing consciousness, furious that this boy’s life had been lost for such a futile cause.”

One always feels guilt when you are not the one.

Disclaimer: Copyright Peter McSporran. The content in this blog represents my personal views and does not reflect corporate entities.

Comments