So rather than talking about the Ukraine war as promised this week, I have picked another very contentious subject, though mainly in farming circles. Regenerative agriculture. As controversial among farmers, as Partygate is amongst British politicians. In implementing this form of production the three contentious issues in my humble opinion are:

Unit competitiveness. That is the unit cost of crop or animal product produced under this regime in comparison to intensive agriculturally produced products, their competition on the supermarket shelf. Despite all the hype to most families in the world, the cost of food is much more important than its origin or production methods. As always the consumer will have the last but most important call.

Environment and climate. Some environments along with climate may influence capability to stick to a regenerative program. I have learnt in farming, never fight the elements, you have to work with them. Flexibility is key although purists may suffer much stress trying to work within parameters not always set by practical agriculturists. Farmers certainly do not need more stress in their daily lives. A study by the Farm Safety Foundation found that 88% of farmers under 40 years old rank poor mental health as their biggest problem!!!

Time for increased management and costs to implement. One is a set quantity, there are only twenty-four hours in a day, the other depends on the model. Most of the successful regenerative agriculture examples I know have spent many years and many dollars in implementing plans and processes to achieve their present success. Often with the support of subsidies not available in the developing world.

“Any steady improvement of the soil is good, make a start by simply not depleting your soil's existing carbon and moisture-holding capacity and build on these. There are no instant fixes in soil improvement.”- Peter McSporran

Rotations of green crops or livestock management in large scale regenerative agriculture have high management requirements often along with perhaps increased labour and equipment inputs. It is certainly not just the laid back attitude often portrayed on YouTube. At what I call ‘hobby farming’ level this is not such a problem but where survival requires a strong bottom line from day one, this then must influence what and how you can achieve your long term goals. In saying that there is no doubt any farmer worth their salt is now giving more attention to the health of his soil.

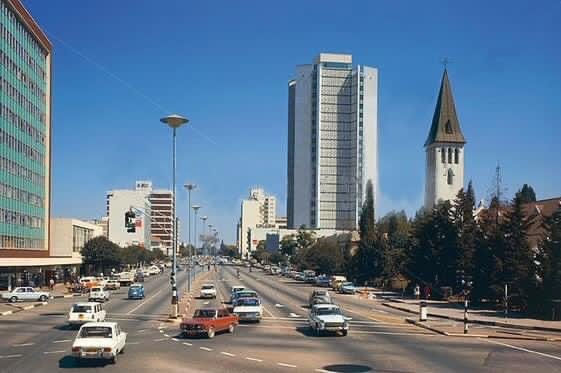

On reflection, we are almost going back to what it was like fifty years ago in the Rhodesian tobacco ‘golden years. Long rotations, mostly grass and legume, between commercial cash crops, incorporation of all crop and ley residues allowing for proper rot down before the next crop. Contours to protect against erosion with dedicated harvesting lines. A seventy horsepower tractor was considered large unlike the monsters of today.

“A corporate fencing off of a piece of natural forest in Africa to publicly proclaim that it is now carbon neutral is neither carbon sequencing nor offsetting, it is deception.” - Peter McSporran

While I understand or rather have my own interpretation of what regenerative agriculture is, I am certainly far from being an expert. In Zimbabwe forty years ago there were many advocates of something similar to this form of production, both crop and livestock. Alan Savory was an advocate of holistic ranching with high-density grazing regimes as one of the tools employed and he is still seen by many as a ‘messiah’ in his field both in Africa and especially America where he was based for many years. If I remember correctly Mike Buttress was such a man on minimum tillage while the director of ART Farm, Richard Winkfield also a strong advocate. His practical demonstrations of reduced tillage saved many farmers money. For myself, the introduction of a chisel plough cost me some profit for the first few years following the removal of the disc plough. Eventually, we were able to give up on the traditional plough; purchasing a chisel plough from Keith Lowe from Radium being both a supplier and strong advocate. Some of the practical farmers from the early nineties who implemented these practices included Brian Oldrieve from Matepatepa who spent much of his time demonstrating its benefits to smallholders in Chiweshe Tribal Trust Land. I believe through a church funded project he still educates smallholder farmers on the principles and benefits of this form of agriculture.

When you look up the definition of regenerative agriculture, there are many contradictions, mostly depending on the geographical location, type of farming and most importantly the individual's idea of what the term means. When I adopted new farming methods, the first two things I would consider were money and time. Money to implement, especially for capital equipment, and the money it would generate - profit! Time is so important as the weather and seasons are always difficult to work around, especially in Africa. I suppose in truth this applies the world over. Windows of maximum opportunity are normally very small so whatever you do regeneratively must be included in these already tight, and more and more variable windows of maximum opportunity. Always the question, will there be the time to implement within the window? Miss the window, you miss a season. No one can afford that!

Nothing worse than starting a program and having to abandon it due to lack of time. Further, the one resource that is always in short supply is your own time. Whatever management system you implement must be within your capability both in time and skill. You must be fully committed, half-hearted attempts in farming always end in failure. Nothing better than a failure to take your enthusiasm and turn it into prejudice. Some of the intensive grazing regimes I have and still view require much daily management. Can they be scaled up? The advocates say yes, however, I have also witnessed some disasters in Zimbabwe where more harm than good was the end result due to management limitations. Easy to do for the first month, even the first year, thereafter forever takes serious dedication. We are always looking at ways to make management easier, not harder.

There is no doubt that many of the advocates of regenerative farming in the media such as YouTube appear to be more ‘hobby farmers’ or those lucky enough to have a local organic market to offer premium prices. There are a number of successful larger operations, although I would add they are more integrated with their methods, more focused on improving the soils and grazing while still adhering to commercial business models. That is to understand the benefits and include them wherever possible in farming programs to both improve the soils and profits. Not always easy.

I claim you cannot look at the one and not the other. It is finding these models that are hard. Even harder is quantifying the financial benefits nearly as difficult as quantifying the level of carbon sequestration. I have seen the yield benefits to some of the better farmers, such as Alan Millar, in Zambia, a long time expedient of zero-till, they are now reaping the financial benefits. However, not without a long and expensive learning curve. Today I eagerly look forward to Mark Butler, also in Zambia, showing his crops and also his rotational cover and break crops. Both these farmers' yields would indicate their soil improvements are certainly paying off. Another who has success with cover crops in rotation is Kevin Gifford in Mozambique. His soils were shot when I first met him. Now he is enjoying improved yields due to the organic matter and improved water holding capacity of the soil.

From what I have seen, be it in cropping or grazing, regenerative agriculture is not about organic farming, irrigation or low chemical fertiliser usage. It is about improving your soil's organic matter, increasing its carbon and water holding ability with the tools and knowledge at hand. Do not exclude on principle something that makes your farming and ranching work for you.

“The cliche ‘if it works do not change it, just for changes sake’ definitely applies to farming.” - Peter McSporran

In the meantime when I look back on my early days when we first started growing tobacco; Kutsaga, that wonderful research station in Rhodesia and Zimbabwe, advocated one-year tobacco, one-year of maize and at least three years of rhodes grass ley which would be incorporated the year before the next tobacco crop ensuring full rot down. By doing this, nematodes challenges were reduced, the soil, mostly sands, improved water holding capacity and there were fewer weeds to deal with. Yes, Rhodes grass would even drown out common couch grass while getting rid of the broadleaf weeds. A limited amount of phosphate and nitrogen was applied to improve seed production or to bulk up hay production.

When irrigation came along, the pressure on the expensive cost of irrigated land brought about rotation change while also offering beneficial tools. Mono-cropping on maize in Zimbabwe was common before the advent of soya in the 1970s. For myself, my irrigated rotation included groundnuts which allowed me to reduce my fertiliser on tobacco, especially nitrogen which I more than halved. It much-improved weed control, and soil fertility which was beneficial to the cattle. The fattest cattle on the farm were those that grazed the groundnut crop residue.

Yes, we do need to think more about our soil health; rotation and cover crops are great tools. Reduce tillage, stop burning crop residues, and introduce green crops. If possible introduce animal production and manage your grazing in a manner suitable for the climatic region. No matter what, overgrazing will destroy natural flora if not carefully managed. Regenerative agriculture is not organic nor irrigation farming although can be included. Organic is probably only valid if it provides a lucrative market while the latter aids with climate mitigation, yet another new farming term. Can we keep up?

Funding allocation seems to get climate mitigation and regenerative agriculture confused. I am still waiting to see a stand-alone regenerative business model which would be a viable project that would attract commercial funding. Not soft sentimental funding, commercial funding!

For the smallholder, land pressure, equipment and training will be the major barriers for them to join the trend. People like Brian Oldrieve’s crusade being one much to be admired.

If you improve your soil by increasing its organic matter, both below and on the surface, nurturing its microbes and therefore increasing its carbon holding and water holding capacity, you are, even to a little extent, practising a form of regenerative agriculture.

Farming in Enterprise

Moving to the Enterprise farming district in 1975 from Nyabira was a major change. While Umzururu had a section of heavy red ‘Hutton’ type soils, the soils were mostly both marginal sandy and acidic. Not easy to achieve high grain yields nor ideal for soya. Insha Allah and High Top farms in contrast were both excellent red soil farms capable of producing high yields of potatoes, onions, soy, wheat and of course maize. On High Top farm, the Edwards also grew both strawberries and onions in the rotation. The third farm they owned which I would move to in my second year was Chifumbi which was more of a sandy loam soil with some black cotton soils.

My move brought new characters into my life along with new farming methods. Although the Edwards had come from Daisyfield Ranch, Somabhula in the Rhodesian Midlands, in Enterprise they were skilled intensive crop farmers. At that time, they were world record holders in maize yields over large hectares. Both Hamish, my previous boss and Les Edwards, my new joint boss, along with Liford, his son, taught me to be prompt every morning and timely (early) in land preparation. In common both had a great knowledge of their labour force including their families. Good labour relations, happy farming. I remember being instructed by Hamish in recognising the important cultural events including understanding the term, extended family. Hamish was a cattleman first who grew crops while Les was a crop farmer who had cattle. In fact, the only cattle on his farms in Enterprise were a herd of pedigree South Devons which were milked for the house and farm workers. The only other breeders I knew owned South Devons in Rhodesia were Ann and Clive Hein from Gweru.

Les did run a butchery which allowed him every Saturday morning to have a social chat with all the surrounding farmers' wives who purchased their meat from him cheaply. In Nyabira most of our neighbours, Lilford, Gilmour, Black and Horseman were cattlemen with cropping while in Enterprise, names such as Staunton, Pascoe, Stobbart, Connor, Ross and Howson were all renowned large cropping farming families. Probably some of the best crop farmers in the country. I do not include tobacco farmers as they stood in a category of their own, although tobacco is a crop. Tobacco farmers generally plied their skill on weaker sandy soils in the more marginal and isolated farming areas of Rhodesia hence suffering most attacks during the war. Red soil farmers always seemed to be closer to the main railway lines and towns. Funnily enough the same applies to Zambia, known as Northern Rhodesia before independence.

Les’s other idiocracy other than running the butchery every Saturday selling cheap meat, certainly cheaper than Orrs in town, was he insisted on being the farm health worker. Often farmer's wives would see to the daily ailments of the farmworkers and their families mainly in the form of malaria treatment pills, mercurochrome for cuts, penicillin for STDs, aspirin for many ailments not exclusively headaches and diarrhoea medicine which came in many forms, the basis of which seemed to have the consistency of liquid plaster of paris. Sticky plasters and bandages were always to hand. Children often burned themselves on open cooking fires or worse accidentally knocked over hot water. Every morning Les would treat all these people requiring his service, be it with a rather gruff bedside manner. Sometimes you wonder about some things throughout your life and for me, this is one.

The other two characters on the Edwards farm were Bert Dodds and Mr Junner. Bert who I have already mentioned looked after the strawberries, onions and pigs on High Top farm. He had become reluctant to share his knowledge as one of his proteges, Nigel Argyll became his biggest competitor on the onion market, in fact, he became the ‘Onion King’ of Rhodesia. Bert was an avid fisherman and introduced bass to the dam on Chifumbe where he could be found rain or shine every Sunday. He had learnt his trade in Scotland, both he and his wife Mary hailed from there. When my father came out to my wedding in ’76 he remarked to me he had never heard anyone as broad as Bert and his wife Mary even in Scotland although they had been in Rhodesia for many years. Bert used to buy liver from the butchery to feed the bass he had in every reservoir on the farm. Bass grow large on a liver diet!

The other character was a very modest man, Mr Junner, also Scottish. He had come to Rhodesia in the 1920s, being elderly his role was to maintain the machinery on the farm. Much of the equipment, as was common on Rhodesian farms, due to sanctions, was old. The Edwards had a fleet of Internationals all loathe to start in the morning which drove Les mad. This made Mr Junner exist in a permanent state of nervous stress.

Mr Junner would tell of his early days in Rhodesia where they thought nothing of travelling to a dance in Insiza near Bulawayo some three hundred and fifty kilometres on a Saturday night. There were not even strip tar roads, only gravel. He also told me they always wore leather condoms when they swam in the rivers as the belief was that you caught Blackwater Fever from a parasite in the water which entered your urinary system through your penis. Mr Junner was also the model of a loving husband. When I met him he was well over retirement age, probably on a very poor salary which mostly went to keep his wife as comfortable as possible. She was bedridden with multiple sclerosis. All his spare time he would spend by her bedside and on occasion would ask me to come and chat with her for a few minutes. A demonstration of true love in every sense by him.

Mozambique Travels Continued

On our travels in Mozambique, I would like to mention two entrepreneurs I got to know down there, both with opposing characters and management styles. One we funded, one we did not. The first, Brendon Evans, I had heard of through his father-in-law, the late Paul Reizlief who had approached me about getting his son-in-law a seed maize quota in Mozambique. Seed Co, of which I was a director, had purchased a seed company there. Having the Government as a partner sealed its demise. Before arriving in Mozambique, I only knew Brendon by reputation. A full-on in your face guy with great ambition supported through thick and thin by his hardworking wife Jenny, a true stockwoman. By the time Han and I met him, he was an established dairy farmer with, in his short time in Mozambique, a fount of sage advice through his experience.

Shortly after arriving in Mozambique, he became aware that all the dairy products in the few supermarkets and large retail outlets in that country were imported from South Africa. It did not take long to find out there were no dairy herds left in Mozambique. There used to be, I knew, for my late father-in-law sold his entire Jersey herd to that country before Independence. Both farmer and cattle were lost during ‘the struggle’. Struggle is the favoured African word for any insurrection war for gaining independence. In most post-independent African countries involved or claiming to be involved at least loosely in the 'struggle’ gave you much recognition if you had a political connection. No political connection, no recognition, only suffering and poverty.

I have sidetracked. Brendon and his good wife Jenny, whose family were very successful farmers and leaders in the Zimbabwean dairy industry, decided milk rather than crops would be a better option. The first lesson; because something is not produced locally does not mean there must be a market. To start the herd, they imported high yielding Holsteins from his in-laws, which flourished in the climate near Harare but unfortunately floundered in the heat of Chimoio. Brendon and Jenny found themselves producing milk with poorly performing cows only to find Mozambicans generally did not drink fresh milk unlike the locals in Zimbabwe where one of the most favoured breakfast meals was maize porridge and Lacto (sour milk). To give them credit, they persevered and identified a niche market for yoghurt and cheeses in Maputo and the many tourist hotels. They set about changing their marketing model along with changing the herd from black and white to the gold of Jerseys which tolerated the conditions much better than the large framed Holsteins. The Evans’ have now left Mozambique but the Danish investors, who were their funding partners, as far as I know, are still in production. Brendon and Jenny, after a good exit, are back in Zimbabwe producing and selling their processed milk products directly to the retailers there very successfully.

My advice to anyone who wants to consider dairy in tropical Africa or in semi-arid areas should go for extensive low-cost production, probably using an F1 cross such as Jersey or Ayrshire crossed with Boran. Be happy with fifteen low-cost litres of milk a day rather than thirty to thirty-five high-cost litres coupled with all the herd health headaches. In Zimbabwe, an example of this was the Africaans dairy farmers in Beatrice who were nearly all cash farmers, pretty unique in that country. Brendon and Jenny’s yoghurts and cheeses for me tasted great, but the lessons they offered Han and I on marketing and the difficulty of dairy production in extreme climates were invaluable.

“Advice from someone with practical experience is worth much more than that from an academic.” - Peter McSporran

I have run out of time again, the second family I want to talk about are Alison and Grant Taylor, another couple with outstanding courage and determination. Next week, their story will fill this section. Oh, bugger, over three thousand words!!!

Disclaimer: Copyright Peter McSporran. The content in this blog represents my personal views and does not reflect corporate entities.

コメント