Missive or Misgivings.

This week, my old friend Vernon Nicolle, whom I have not seen for many years, sent me, and I am sure many others, what he describes as his missive. In fact, a letter explaining his views or perhaps better described as his visions on compensation for displaced Zimbabwean farmers known acronymically as TDHs within the present state of play. He also included a couple of personal lines to me, both with a viewpoint completely opposing mine. I am not going to argue with him in public; we are all allowed our views, and his view would be correct if we trusted our Zimbabwean government. I doubt he does, which reminds me once again of my old-school motto.

“Persevere in Hope.”

I agree that we have to deal with the Government in power in our deliberations, even in our efforts to try and obtain compensation. I may add not just for improvements but also for our confiscated land in the future. Hence, I am reluctant to give up my title for a chance of receiving a portion of the compensation due. What is on offer is for only the improvements. In saying that, if it were a genuine offer in cash, many of us would take it and run. I agree with him that my understanding of the reality of the situation may be misplaced, but there is little chance that his vision of events will come to fruition.

“I have found in my life and businesses that doing any form of transaction with someone you mistrust, from experience or reputation, will always end in a loss to yourself in some form.” - Peter McSporran

For any meaningful compensation, no matter how much and when paid, there will have to be a legitimate legal agreement between the farmers and the Government, individually, probably under some umbrella agreement. As Vernon says, Zimbabwe has the Government it has. I agree, and as we well know its track record, the utmost caution must be taken in developing any agreement with it. No matter if it does not suit everyone, such an agreement must have international recognition and guarantees to make it worth anything. It will have to be a holistic agreement in its structure to look at the broader recovery of Zimbabwean agriculture rather than just compensating white displaced farmers. Hence, my scepticism about the present offerings by the Government which seems exceedingly proactive in promoting the present agreement. A good reason to make one cautious.

“The present Zimbabwean Government is one of the most avid and poorest presenters of window dressing. Its actions soon destroy any myths it tries to create.” - Peter McSporran

I am told that the recent $50 million bond issue they tried to market on the Victoria Falls Stock Exchange was to help towards compensation due to TDHs mentioned in this year's budget. No surprise they failed to do so. Was it once again just an exercise in window dressing? The recent national budget was one of desperation; in real terms, they are still taxing the lowest-paid workers while adding costs to their living expenses, such as transport, with increased fuel levies and tolls. Now a wealth tax on homeowners, once again based on US$ values. Where will the Government find the funds to pay farmers if it is struggling to find them to run itself?

Two bizarre non-happenings that have struck me as surreal about the actions of those who believe they represent us, TDHs, have arisen this week. The first is the non-disclosure of the details of the agreement that PROFCA and Vernon, as an advocate, are promoting. Surely, if you are marketing something, you show the goods? The second instance is that in this month's CFU Calling for December, the CFU's in-house newsletter, there is no mention of the fact there is a constitutional crisis in the union, with the election of its President having been delayed well out of the guidelines of the constitution of the organisation. The present President is still in place under default, not election. No mention, why! Luckily, there is now a legal opinion, instigated in part by the Past Presidents and others, which is now available to guide the council in resolving the crisis.

Vernon, in answer to your missive, mine is only misgivings. I do not see a legitimate agreement in the near future. In saying this, I hope some early relief can be found for the desperate.

Marketing Changes.

It had been in the air for a number of years. The marketing systems that made Rhodesia and later the new Zimbabwe the envy of the world, let alone the region, were about to be abandoned for better or worse. In 1990, Zimbabwe launched a five-year Economic Structural Adjustment Policy (ESAP) financed by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and Western donor countries. It was meant to bring in a free market economy which would be competitive in the export market. Prices, including those for agricultural commodities, would be market-driven. Until this time, agricultural food commodities, including beef and cotton, were fixed by negotiation between the farmers' unions and the Government, traditionally with the Government keeping an eye on food security and the cost of living while ensuring adequate production. The trouble is the then Government did not understand that any action on pricing has a built in lag. Viable prices announced today will only promote production the following year, only if they are seen as keeping up with inflation. The poor maize prices to provide cheap food to the voters in the late eighties ensured empty silos when most needed in the 1992 drought.

Despite this, margins were made in most commodities, and stability in the marketplace and production base ruled. As the years passed from Independence, food prices became used more as a political tool and huge distortions were brought into play in the marketplace, with the marketing boards’ often having unfunded losses to carry as the Government tried to buy votes even at times reducing the boards’ selling prices for maize below its buying price. This was a great way to make money if you were an unscrupulous trader with political connections. Trucks at depots were seen buying maize and just a few hours later delivering the same maize to make a margin.

Under ESAP, this would change; market prices through demand and supply would prevail. Sadly, like many political ideas, the stated policy and implementation were poles apart. Because of this, coupled with ESAP, we had to look at new agricultural marketing systems as the Government wanted to remove subsidies—the foreign supporters of ESAP were adamant about this. We felt badly done as we knew most of their own home agriculture survived due to heavy subsidies. The main exception to all this upheaval was tobacco. Although it had a marketing board, it had always been sold through an auction system as it was close to 100% export-oriented.

One of the wonderful things about the old marketing system was that prices did not vary geographically; for example, maize delivered in Mutare would be the same price in Karoi. The parastatal marketing boards absorbed the logistical costs; they were built into the nationwide commodity prices. In reality, the producer was the one that really carried the cost, the difference in his price to the ongoing selling price to the miller or processor. That was up until political interference and corruption in the system. There were many depots spread around the country, which made delivery very easy, often just with a tractor and trailer or, in the smallholder areas, even an oxcart. The older commercial farmers were reluctant to accept that change was coming, but it was.

“One of the hardest things for farmers to accept is change. Many farmers went broke doing what his father did before.” - Peter McSporran

The Government felt the small-scale farmers could produce the country's food needs in the form of maize, while cotton would be their main cash crop. Hand-picking cotton was labour-intensive. Once again the Government was happy to put the wages up for commercial farmers but argued that intensive labour operations like harvesting cotton could be done cheaper by smallholder farmers. This was, in truth, only because they and their families almost worked as slaves with little reward for their labour. It was suggested that commercial farmers should look at producing the more agronomically difficult and expensive to produce crops such as wheat, soya, plantation and export horticultural crops. Sheep and goats never had any formal marketing system, while cattle did through the Cold Storage Commission (CSC). They once again had an imposed monopoly, especially with the sole right to export beef by the CSC. As I said, the Government adopted ESAP but did little to cushion the trauma of transition, let alone put in place alternate marketing structures.

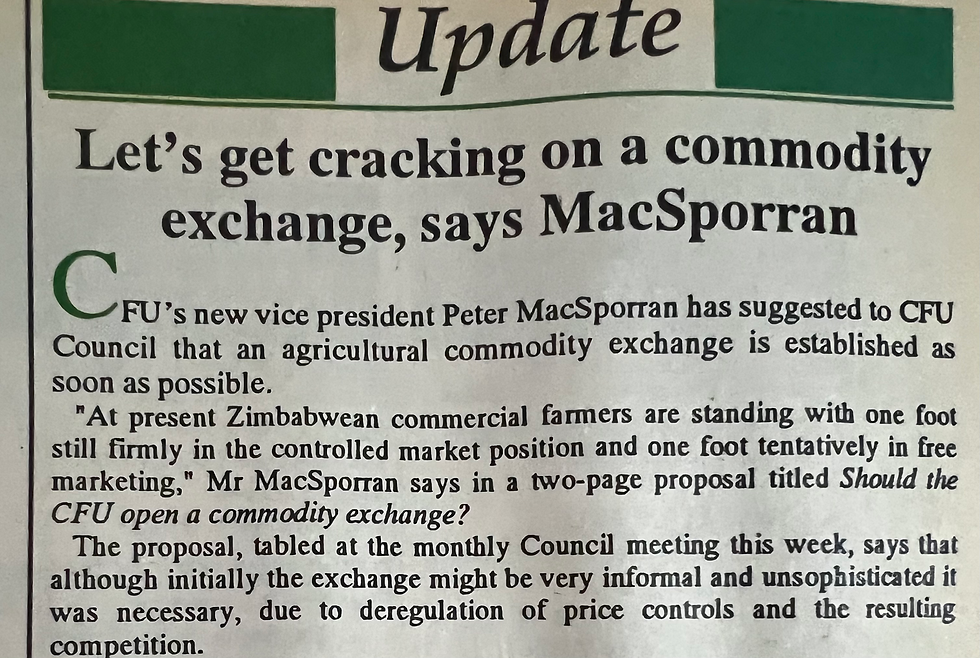

At the December 1992 Commercial Farmers Union (CFU) Council meeting, I proposed introducing a commodity exchange to cater to those commodities being released from Government control and pricing. I must say Alan Burl had raised the same idea at the CFU Congress a couple of years earlier, but then the seeds were being planted too early for germination to take place.

This would be a huge step into the unknown for Zimbabwean commercial farmers. After much debate at the council, it was agreed to pursue the idea further, with me heading the initiative. Interestingly, at the same meeting, Oliver Newton, Chairman of the Winter Cereals Association, suggested the CFU should look at its own structure as the collection of crop and livestock levies would become much more difficult in future with free marketing. Up till then, levies were conveniently collected by the marketing boards for distribution through the various farmer unions to the associations. For example, the winter cereals (wheat) levy was collected by the Grain Marketing Board, a single agency. In contrast, the free market levies would have to be collected from multiple millers, traders, and even speculators. Strangely enough, while the old hands accepted the concept of a possible commodity exchange, they were reluctant to look at our own structures for catering to the future. In a couple of years, Oliver was proven correct, and the union went through a massive review of its structures, services and funding. To collect levies in the future, the Commodity Associations had to become much more proactive in representing their members. It was not a given they would receive a fair price for their crops and livestock, let alone pay levies.

Disclaimer: Copyright Peter McSporran. The content in this blog represents my personal views and does not reflect corporate entities.

Comments